The Operation: Lap Band Surgery

[media id=74 width=500 height=400]

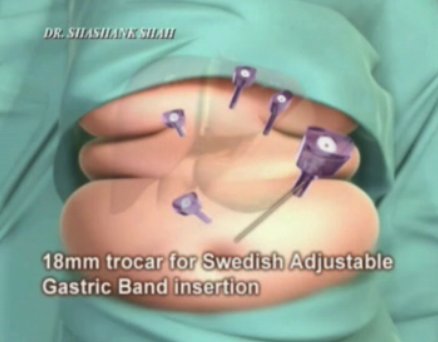

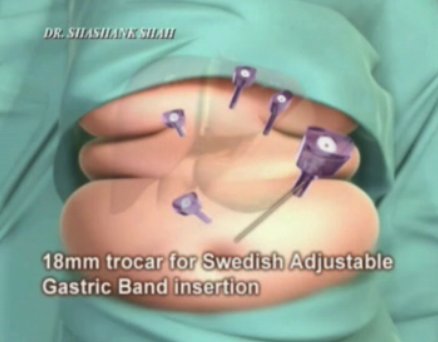

The Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding Procedure (also know as lap band surgery) is performed under anesthesia in a hospital operating room. During surgery, three to five one-half inch to two inch incisions are made in the upper abdomen. Barring any complications, the procedure usually takes about 50 minutes to one hour to perform.

All patients undergoing this procedure need to be aware of the possibility of complications such as adhesions from previous surgeries which may make a laparoscopic procedure impossible. In this case, the surgeon will convert to an open procedure with a five inch incision and longer recovery period.

Many surgeons allow patients to return home the same day; however, other surgeons require patients to stay overnight before they are released from the hospital. If this occurs they are usually released about 24 hours after surgery. Although most lap band patients feel quite well after two or three weeks, full recovery usually takes approximately six to eight weeks. When you are ready to leave the hospital, you may receive a visit from the hospital dietitian who will go over the required diet for Lap-Band patients

Lap band fully detailed

During the lap band surgery a smaller stomach pouch is created in the upper portion of the stomach. Normally, this pouch will only hold approximately ½ to 1 ounce of food. This pouch connects to the rest of your stomach through an outlet called a stoma. You will feel full when your upper stomach is full and as a result you will be able to control your eating habits and over time, with the right eating habits, you will start to lose lots of weight. And it’s natural weight loss so once you lose the pounds they won’t just fly back on.

In essence, the lap band surgery is a procedure aimed to promote weight loss for people who are severely struggling to cope with obesity. Here’s how it works in greater detail:

A ‘gastric band’ with a small balloon inside is attached around the top portion of your stomach, forming a smaller ‘gastric pouch’. The placement of the band creates a small pouch at the top of the stomach that holds up to approximately 30 ml, which works out to about 1/8 cup. You are inclined to eat less because the pouch holds less food than the whole stomach. As the upper part of the stomach registers itself as being full, it sends a message to the brain saying that the entire stomach is full. This is the main principle behind the lap band procedure; this tightening of the stomach feeling or sensation helps the person to:

1. be hungry less often

2. to eat smaller portions

3. and lose weight over time.

This pouch is filled with a saline solution which is injected into the band via a port. Via the port, the surgeon has control over the amount of saline solution that is inserted into the band. When adjusting the lap band (same as gastric band) a specialized needle must be used as to avoid causing any damage to the port or the port membrane. When fluid is injected, the lap band expands and places pressure around the outside of the stomach. This causes a decrease in the size of the passage between the pouch and the lower stomach; restricting the movement of food.

After the procedure, the next stage is the post lap band surgery follow-up adjustments. During this stage, the patient will need to visit their doctor every few weeks in order to receive their saline injections. Over time, the band is filled to the point where the patient feels they’ve hit a ’sweet spot’ where optimal restriction has been achieved. The key to living post-lap band surgery is to follow the lap band diet, which is described on our lap band diet page.

Lap Band, Lap Band Health, Lap Band Health Latest, Lap Band Health Information, Lap Band Health information, Lap Band Health Photo,Lap Band for Weight Health photo, Lap Band Health Latest, Lap Band Health latest, Lap Band Video, Lap Band video, Lap Band Health History, Lap Band Health history, Lap Band over Picture, history, Lap Band Asia, Lap Band asia, Lap Band Gallery, Lap Band for Weight gallery, Lap Band Photo Gallery, Lap Band Picture, Lap picture, Lap Band Web, Malaysia Health, web Health, web Health picture, video photo, video surgery, gallery, laparoscopy, virus, flu, drug, video, Health Health, calories, photo, nutrition, health video, symptoms, Lap Band , medical, beating, diet, physical, Training, organic, gym, blister, exercise, weightloss, surgery, spiritual, eating, tips, skin, operation, bf1,