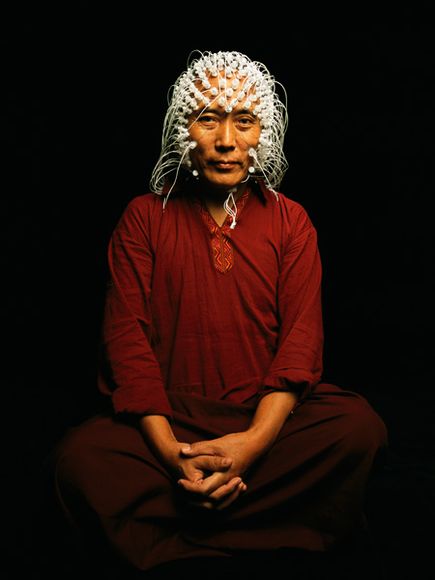

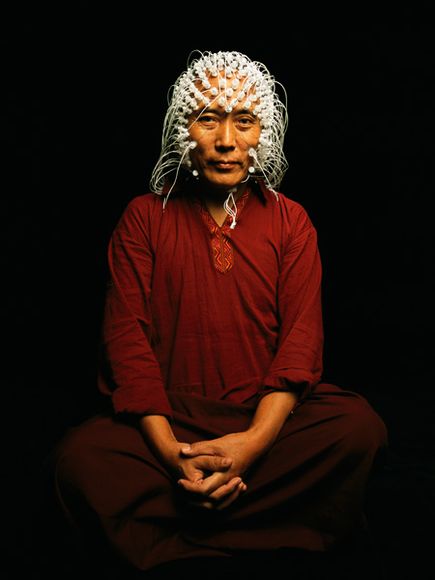

Electrodes measure a Tibetan monk’s brain activity.

Electrodes measure a Tibetan monk’s brain activity.

The ancient Egyptians thought so little of brain matter they made a practice of scooping it out through the nose of a dead leader before packing the skull with cloth before burial. They believed consciousness resided in the heart, a view shared by Aristotle and a legacy of medieval thinkers. Even when consensus for the locus of thought moved northward into the head, it was not the brain that was believed to be the sine qua non, but the empty spaces within it, called ventricles, where ephemeral spirits swirled about. As late as 1662, philosopher Henry More scoffed that the brain showed “no more capacity for thought than a cake of suet, or a bowl of curds.”

Around the same time, French philosopher René Descartes codified the separation of conscious thought from the physical flesh of the brain. Cartesian “dualism” exerted a powerful influence over Western science for centuries, and while dismissed by most neuroscientists today, still feeds the popular belief in mind as a magical, transcendent quality.

A contemporary of Descartes named Thomas Willis—often referred to as the father of neurology—was the first to suggest that not only was the brain itself the locus of the mind, but that different parts of the brain give rise to specific cognitive functions. Early 19th-century phrenologists pushed this notion in a quaint direction, proposing that personality proclivities could be deduced by feeling the bumps on a person’s skull, which were caused by the brain “pushing out” in places where it was particularly well developed. Plaster casts of the heads of executed criminals were examined and compared to a reference head to determine whether any particular protuberances could be reliably associated with criminal behavior.

Though absurdly unscientific even for its time, phrenology was remarkably prescient—up to a point. In the past decade especially, advanced technologies for capturing a snapshot of the brain in action have confirmed that discrete functions occur in specific locations. The neural “address” where you remember a phone number, for instance, is different from the one where you remember a face, and recalling a famous face involves different circuits than remembering your best friend’s.

Yet it is increasingly clear that cognitive functions cannot be pinned to spots on the brain like towns on a map. A given mental task may involve a complicated web of circuits, which interact in varying degrees with others throughout the brain—not like the parts in a machine, but like the instruments in a symphony orchestra combining their tenor, volume, and resonance to create a particular musical effect.

Corina’s brain all she is…is here

Corina Alamillo is lying on her right side in an operating room in the UCLA Medical Center. There is a pillow tucked beneath her cheek and a steel scaffold screwed into her forehead to keep her head perfectly still. A medical assistant in her late 20s, she has dark brown eyes, full eyebrows, and a round, open face.